Specialised / Monitored Exercise Prescription

An exercise prescription, like any prescription, has a type and dose, a dosing frequency, a duration of treatment, a therapeutic goal, and anticipated adverse effects. This is true whether the exercise is simple stretching for range of motion, aerobic exercise for all around fitness, resistance training for strength, or a more integrated type of functional exercise designed around activities of daily living.

Exercise prescription for special individuals

1.

What is Exercise Prescription ?

The World Health Organisation describes exercise as ‘a subcategory of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposeful in the sense that the improvement or maintenance of one or more components of physical fitness is the objective’. Hence, increasing your physical activity level may include exercise as well as other activities, which involve bodily movement, in playing, active transport, (walking or cycling for example), house chores, and recreational activities.

An exercise prescription, is a recipe for undertaking exercise (endurance, strength, balance, and flexibility) and like any prescription, has a type and dose, a frequency of the dosage, a duration of treatment, and a therapeutic goal. This is true whether the exercise is simple stretching for range of motion, aerobic exercise for all around fitness, resistance training for strength, or a more integrated type of functional exercise designed around activities of daily living.

Generically speaking, any exercise prescription resembles a drug prescription: Exercise A, taken N times daily, for (X) duration of weeks/months/years. The exercise type and dose are also tailored from American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines, person’s individual needs, goals, and ability level.

2.

General Exercise

What exercise dosage is the minimum recommended

Adults aged 19–64 years should aim for 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity in bouts of 10 minutes or more (that is, 30 minutes at least 5 days a week).

Comparable benefits can be achieved through 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity spread across the week and at least 2 days of the week activity should be aimed at improving muscle strength.

Although the guidelines for people over 65 years are similar, older adults are encouraged to include activities that improve balance and coordination, especially if at risk of falls.

At Med-Ex we tailor specific programs to patients health condition, as there are specific exercises prescribed by the ACSM that have been medically proven to assist with health and wellbeing. The frequency, intensity, time and type, (FITT) of each session are carefully matched to person’s intrinsic functional fitness taking also into account exercise recovery. The progression of any programme is determined by combining recommended ACSM guidelines, a person’s intermediate and long term goals and most importantly background medical condition(s).

3.

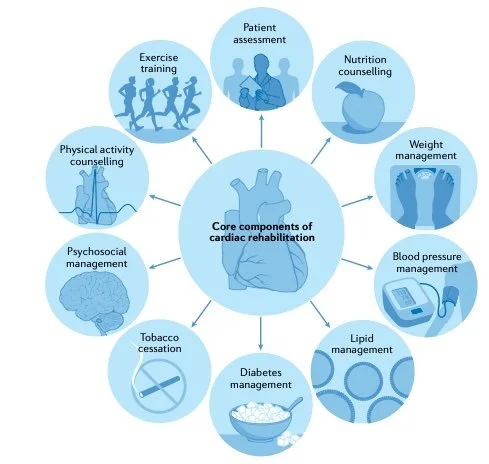

Integrated Monitoring of Cardiac Rehabilitation

A growing body of RCT evidence over the past 3–4 decades now supports contemporary clinical guidelines, which recommend routine referral for cardiac rehabilitation across a range of cardiac diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome, heart failure and after coronary revascularisation (PCI or CABG surgery) [1].

Several cardiac rehabilitation programmes are now using a hybrid approach to deliver cardiac rehabilitation. For example, this approach initially offers patients centre- based cardiac rehabilitation and then evolves to longer-term maintenance through technology- supported, home- based sessions. The effectiveness of these innovative models is likely to depend on active, ongoing contact between patients and health- care professionals through more traditional methods, such as home visits and telephone consultations, with the use of technology- based solutions [2,3].

Our challenge perhaps today is to find a better clinical care paradigm in which doctors, allied health professionals such as nutritionists and exercise specialists (such as ourselves) work more closely together to provide medically integrated exercise programmes that are appropriate for each patient.

Hippocrates wrote,

‘‘In a word, all parts of the body which were made for active use, if moderately used and exercised at the labor to which they are habituated, become healthy, increase in bulk, and bear their age well, but when not used, and when left without exercise, they become diseased, their growth is arrested, and they soon become old.’’[4]

We focus our prescription on monitor exercise using 1) ECG, 2) Ambulatory BP and 3) frailty (strength and ROM) and gait analysis to track exercise progression very carefully. This allows any change to be documented and referred.

Taylor R.S., D. H. M., McDonagh S.T.J. (2022). The role of cardiac rehabilitation in improving cardiovascular outcomes. Nature Reviews. Cardiology, 19(3), 180-194.

Imran, H. M. et al. (2019) Home-based cardiac rehabilitation alone and hybrid with centre-based cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012779.

Thomas, R. J. et al. Home-based cardiac rehabilitation: a scientific statement from the American association of cardiovascular and pulmonary rehabilitation, the American Heart Association, and the American College of Cardiology. J. Am. Coll.

Hippocrates. On the articulations. The genuine works of Hippocrates, translated from the Greek with a preliminary discourse and annotations. London: Sydenham Society, 1849, circa 400 BC:part 58.

Exercise is Medicine

Physical inactivity is one of the 10 leading causes of death in developed countries and results in about 1.9 million preventable deaths worldwide annually. The benefits of physical activity on various health issues including atherosclerotic vascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, dyslipidemia, obesity, mental health, and a reduction in mortality, are now undisputed. In addition, a sedentary lifestyle is shown to be a more significant risk factor for coronary artery disease than other ‘established’ risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia. There are also positive economic benefits of physical activity programmes to communities, corporations and public health, shown by cost–benefit ratios. Less openly known and discussed benefits of exercise include prevention against certain cancers, with studies demonstrating that physical inactivity can almost double the risk of developing colon cancer with other cancers such as breast, prostate, and lung following close behind.

What Does Regular Exercise Achieve

Regular physical activity using large muscle groups, such as walking, running, or swimming, produces cardiovascular adaptations that increase exercise capacity, endurance, and skeletal muscle strength. Habitual physical activity also prevents the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and reduces symptoms in patients with established cardiovascular disease. There is also evidence that exercise reduces the risk of other chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, [1 ] osteoporosis, [2] obesity, [3] depression, [4] and cancer of the breast and colon [5,6 ].

Physical activity is also an important adjunct to diet for achieving and maintaining weight loss. The National Weight Control Registry [US] enrolled 3000 individuals who lost >10% of their body weight and maintained this weight loss for at least 1 year [3]. The average weight loss of 30 kg was maintained for an average of 5.5 years. Eighty-one percent of the registrants reported increased physical activity. Women and men, respectively, reported expending 2445 and 3298 kcal weekly in such activities as walking, cycling, weight lifting, aerobics, running, and stair climbing.

References

1. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al, for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346: 393–403.

2. Vuori IM. Dose-response of physical activity and low back pain, osteoarthritis, and osteoporosis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001; 33 (6 suppl): S551–S586.

3. Wing RR, Hill JO. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001; 21: 323–341.

4. Pollock KM. Exercise in treating depression: broadening the psychotherapist’s role. J Clin Psychol. 2001; 57: 1289–1300.

5. Breslow RA, Ballard-Barbash R, Munoz K, et al. Long-term recreational physical activity and breast cancer in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I epidemiologic follow-up study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001; 10: 805–808.

6. Slattery ML, Potter JD. Physical activity and colon cancer: confounding or interaction? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002; 34: 913–919.